Four years ago, Natalia Melikova hadn’t even heard the word constructivist. Now the Academy of Art University graduate has returned to Russia to save remaining examples of constructivist architecture there—through photography. Her Constructivist Project aims to protect these bold and provocative examples of the 1920s and ’30s avant-garde from neglect and haphazard development.

Melikova (MFA Photography 2012) says her interest in the Russian avant-garde was sparked in her first semester at the Academy by a class assignment: to copy the work of a master photographer. She chose the groundbreaking post-WWI artist, graphic designer and photographer Alexander Rodchenko. The result, she says, was a revelation. “I looked up his work and was immediately attracted to the dynamic compositions, the beautiful lines and the unconventional perspectives of his photographs. Turns out, photography was just one of his many talents, and my increasingly involved exploration of his work led me to take a strong interest in the art and aesthetics of his time.”

Constructivism, which Rodchenko helped found, was a pre-Soviet flowering art and architecture in Russia in the 1920s and ’30s, part of the global interest in modernism. Constructivism’s emphasis on solid lines and planes, minimal decoration, and its reliance on modern industrial materials tie it to the Bauhaus movement, taking place contemporaneously elsewhere in Europe.

While in Moscow working on her thesis for the Academy, Melikova saw the poor condition of constructivist buildings and began looking into their future. Now based full-time in Moscow, she says she’s hoping to use her photography “for a good cause, by shining a light on these buildings I find so interesting.”

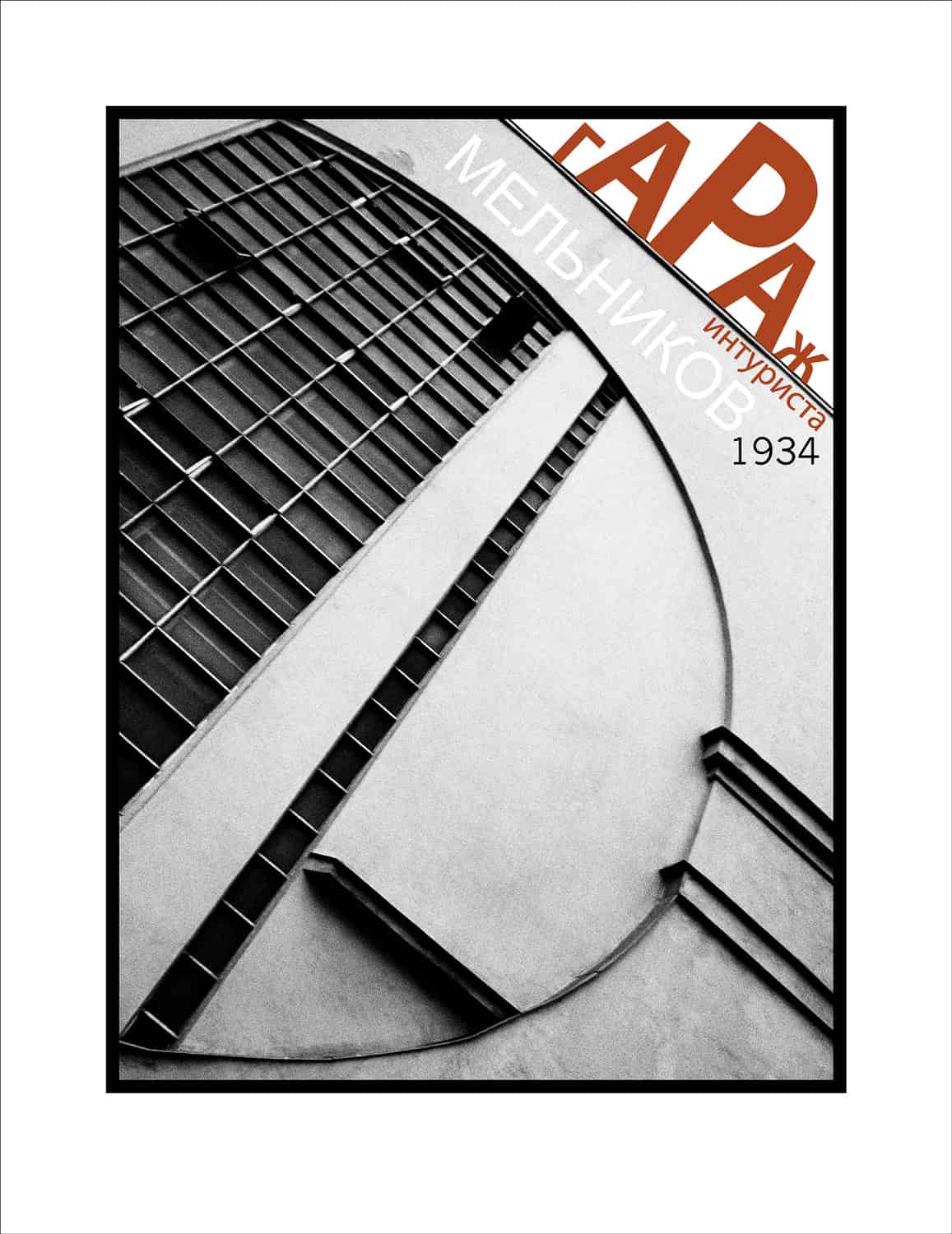

To help raise awareness, she has also developed a series of elegant screen-printed and digital posters depicting significant landmarks from the movement. The posters incorporate typography and design that recall constructivist graphics of the era.

There’s a reason for her sense of urgency: Constructivist buildings in Russia are abandoned or deteriorating, and many are threatened with demolition for new developments. While admitting she’s not an expert in historical preservation, she says her passion and her ability to visually communicate the importance of these landmarks give her a unique perspective on their prospects for survival.

The architectural community in Moscow may be passionate about preservation, she notes, but “somehow those in positions of authority show indifference towards historical buildings, and have the attitude that new is automatically better.” This short-term thinking is familiar to preservationists worldwide, putting historical buildings at risk. “The fact that historical buildings find themselves on prime real estate puts them in danger of interfering with new developments, so ways are found to convince authorities that the buildings are not safe and should be demolished.”

Often the public is poorly informed as to the value and potential of historic structures. “When I was photographing for my thesis, people would come up to me and ask why I was photographing ‘that old building.’ I admit, to ordinary passersby, these are just old buildings. But architecture reflects the times in which it was built. And I think if more people learned about the historical context, why the style is the way it is, there would be more understanding of the value of historic buildings in the Moscow cityscape.

“And that is one of the aims of The Constructivist Project: to inspire others to become curious about their surroundings.”

Melikova’s experiences studying at the Academy of Art University helped her develop the habits of creative thought that led to the project. “I did not come from an art or photography background,” she says, “so I think the most valuable thing I learned at the Academy was how to think about photography and ask the question, ‘Why?’”

Her formally dynamic and technically proficient architectural photographs both depict and embody the past glory and present peril of these important structures, and her work poses powerful questions as to why they are underutilized and all too often sacrificed on behalf of yet another luxury apartment complex.

Melikova is receiving public notice for her devotion to Russia’s constructivist heritage, but due to the urgency of some cases, she’s lately had to devote more time to campaigning on their behalf than photographing them. “When things settle down and the weather gets more friendly,” she says, “I hope to get back to photographing the architecture!”